By Sarah Slocum

You’re 65 and you’ve worked all of your adult life, saved up a nest egg, earned a pension, saved in a retirement account, and paid into Social Security and Medicare. You have a pretty nice retirement income and lifestyle. Now suppose you need long term supports and services (LTSS) at some point in your later years, as most of us will. Very likely, you face disaster! Many otherwise well-informed Americans don’t realize that Medicare does not pay for LTSS; it only covers short term stays after hospitalization in a skilled nursing facility and limited periods of skilled home health and hospice care. That means if you live a couple of years needing paid daily help, you will have to pay for that all out-of-pocket – or spend down to Medicaid. And that means you will forfeit essentially almost all of your assets and income.

Medicaid pays for about two-thirds of all long term nursing home stays. Although the default is care in a nursing home, most states increasingly provide home and community-based services (HCBS) and are taking steps to shift funding toward in-home LTSS. But Medicaid is complicated and varies state by state, with complex, changing rules on functional and financial eligibility. Federal law sets some rules that states must follow in designing their Medicaid plans, but many crucial decisions are up to each state. The range and scope of LTSS options that states offer, like the Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and various HCBS initiatives vary enormously, since they are optional and states can choose whether and how to offer them.

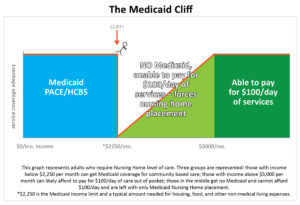

For people who need LTSS, one of the most difficult aspects of understanding Medicaid is that in many states, including Michigan, there are stricter (lower) income amounts that are required to qualify for community-based options as compared to nursing home care. Right now, Michigan has a strict cap on income for PACE and HCBS that is set at $2,250 per month. This amount is 300% of the income limit for the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI). It is treated as a hard cap, meaning that a person who has even one dollar more than $2,250 from all retirement income sources combined is not eligible for Medicaid covered PACE and HCBS services. This is also known as the Medicaid cliff. The result is that if your income is below that amount, you can get a range of services that are adequate for your support. If it’s above $2,250, you have to “make do” with inadequate services and serious risks to health and life, or give up virtually all of your income and enter a nursing home. It makes little sense that someone with income over $2,250 per month can still get Medicaid support for an in-patient nursing home stay, but not for staying at home, usually at less cost to the state. According to David Goldfarb of the National Academy of Elderlaw Attorneys, “Experts often talk about the importance of generating lifetime-income in retirement. Unfortunately, our long-term services and supports system is in direct conflict with this goal. Some individuals learn the hard way that doing the right thing leaves you with no choice but the nursing home.”

Some states mitigate this pressure by allowing special arrangements to set aside excess income through trust mechanisms like Miller Trusts, Pooled Trusts, or Special Needs Trusts. New Jersey received a waiver from CMS a few years ago to allow people with excess income to set aside enough to become eligible and use those funds later for non-covered medical and LTSS expenses. Many states, though, have failed to address the disparity, leaving people who have just a little more income than the limit with no real choice but to move into a nursing home to get basic supportive care. This means that if you had savings enough for your first year or two of disability, but if your income is just a little above the Medicaid limit – you could find yourself having to cope without critical services like adequate food, heat and hygiene. Or you might have to give up your home and income, and enter a nursing home.

Below is a graphic that illustrate these points. It applies to a great many states, though some have learned to enable HCBS services in a way that eases the cliff.

In addition to allowing various trust arrangements to set aside excess income, other possible solutions include allowing people to participate in cost sharing for their services, so that Medicare beneficiaries would pay for LTSS with the portion of their income that is over the hard cap, and Medicaid would pay for the rest of the month’s LTSS. This would allow people to participate in Medicaid programs through paying a premium to the state, or establishing a deductible that is based on the amount of income the individual has above the cap. None of these options seem terribly difficult — what has been lacking so far is the political will to change Medicaid policies in states that have an artificially low Medicaid cliff.

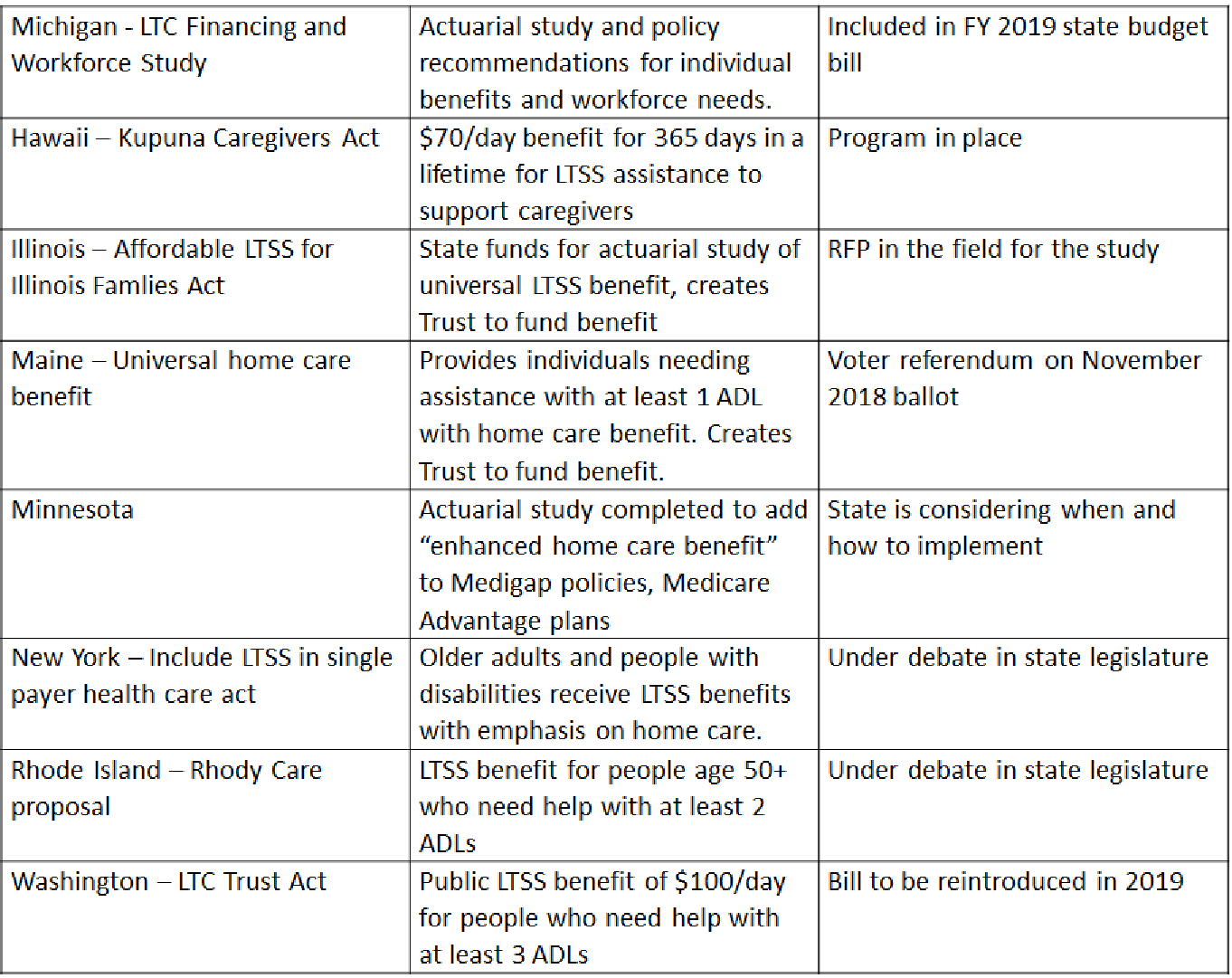

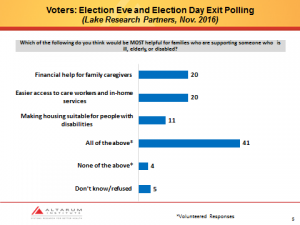

Altarum is researching these possible options and working to build public momentum to address the disparity in income caps that exist for institutional care vs. HCBS. We think that newly elected state leaders may want to join their colleagues in exploring ideas and taking action to make it possible for those who want to age in place through to the end of life. To make this a reality, we need to extend access to PACE and HCBS as a win-win for elders who need LTSS and for state budgets.

Is your state like Michigan, with a low income cap for HCBS? If you’re not sure, ask your Medicaid office or a geriatric social worker. Are you interested in joining our efforts to influence states that to stop tolerating a Medicaid cliff? Reach out to us at Altarum, by sending an email to [email protected]. We want to support your efforts and join them with ours to make policy changes that create more rational and accessible LTSS options.