Authors Anne and Nils

By Anne Montgomery and Nils Franco

As the age wave rapidly transforms Medicare and the wider U.S. health care sector during the 2020s, policymakers and stakeholders are starting to pay much closer attention to including supportive services as part of the continuum of health care delivery. A growing number of Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are now offering certain limited supplemental long-term services and supports, such as transportation and personal care. Community-based organizations (CBOs) are eager to expand to provide these and other services, and more Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) are forming networks in order to contract with a range of health care organizations. And in the Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) sector, an expanding array of Alternative Payment Models (APMs), starting with Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), are being developed and implemented to incentivize both practitioners and beneficiaries to shift toward more coordinated models of service delivery and tighter financial integration.

Following is an examination of an array of models that are aiming to foster better coordination, quality oversight, and efficiency in care for tens of millions of Medicare beneficiaries who need both medical care and supportive services.

Current Transformative Models in Medicare

At their core, Medicare ACOs are hubs of doctors, hospital(s), and other medical care providers that share financial and clinical responsibility for providing good care while also limiting unnecessary spending. Where successful, ACOs receive incentive payments that reflect a share of Medicare spending reductions for patients attributed to them. They can take on various structures of ownership, risk and decision-making power held by constituent medical practices. The Direct Contracting (DC) model recently announced by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) may prove attractive to a subset of ACOs, because it offers greater flexibility for contracting with non-medical organizations, and it lets participating entities capture a larger share of savings (by taking on more downside risk). Direct contracting may attract other types of health care organizations, including some PACE (Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly) plans.

In related work, CMMI is encouraging more comprehensive care planning and service provision by primary care practices through medical home models. The Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) initiative, for example, pays medical home practitioners to coordinate their patients’ primary care and their referrals for certain tests and specialists. Medical home practitioners are also eligible to receive a modest bonus tied to achieving benchmark quality measures such as lower preventable hospital readmissions or patient-reported care coordination. Notably, the CPC+ model requires participants to “identify patients’ high-priority health-related social needs and resources available in your community to meet those needs.”

Starting in 2021, CPC+ will evolve into the higher-risk Primary Care First (PCF) model, in which primary care practices will help their patients follow through on all services for which they are referred. Both clinical quality and patient experience measures – including use of advance care planning as well as patients’ survey responses, blood pressure and glucose levels, and cancer screening rates – will be used to determine which PCF practices are eligible for bonuses. The PCF model also ties payment to attributed beneficiaries’ overall Medicare spending. To succeed in this model, therefore, practitioners must be able to effectively track their patients across multiple care settings.

A more specialized PCF model for seriously ill beneficiaries whose care is hard to predict – those who frequently use the emergency room and incur high hospital costs, and who lack a consistent primary doctor – will also be implemented. PCF practices must change seriously ill beneficiaries’ pattern of health care, and they must establish a cohesive plan to link and track these patients with other medical and social services providers.

Together, these CMMI models, especially newer forms that pay flat amounts per beneficiary, have the potential to provide a new source of referrals to CBOs and to thereby expand the reach of supportive services to the frail and chronically ill elderly. For the medical sector, the new models are making physicians and hospitals more aware of the social needs of beneficiaries they see. In ACOs and in MA plans, screening for social determinants of health (SDOH) has translated to only modest growth in referrals for supportive services to date. But actually connecting patients to a reliable source of supportive services is key to keeping beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions out of crisis. Closer business and service delivery relationships between CBOs and medical providers are needed to reduce costs and improve care.

Partnered Efforts for Population Health in the Community

Screenings are fundamental to the Accountable Communities for Health (ACHs). The movement gained steam through CMMI’s State Innovation Models, and AHCs now have funding for screening for supportive care needs and navigating Medicare and/or Medicaid enrollees to community resources under a demonstration that runs from 2017 through 2022 (the Accountable Health Communities Model). In general, ACHs are local collaborations that ask the public health, social services, and medical sectors to act together in order to address social issues that face their constituents and affect their health. A medical partner or other “bridge organization” conducts screenings, and the ACH works with supportive services providers to try to ensure that referred clients are linked to follow-on services.

While ACOs and primary-care medical homes receive medical system dollars to conduct screenings and to send referrals to CBOs, CMMI’s model for ACHs includes public health agencies, LTSS providers, and CBOs, and investments in IT infrastructure and capacity can be shared among participating organizations. The demonstration’s bridge organizations include a broad range of medical and non-medical groups: they include hospital systems, public health departments, and direct service nonprofits. There are also ACHs with other sources of funding. Overall, ACHs aim to create change “through integration with delivery and payment system reform, and funded by both private and public payers,” according to a 2017 survey, which notes that to date, some ACHs have been slowed by the capacity of partners to raise start-up funds and to communicate across organizations.

Catalysts Needed to Continue Innovation and Coordination

Additional reforms are needed, as illustrated by a 2018 survey (Bleser et al, Health Affairs, June 2019) of ACOs serving seriously ill Medicare beneficiaries, which identified significant infrastructure deficits in data, analytics, social supports and workforce. Surveys of CBOs and AAAs about their contracts with the health care sector have identified persistent barriers to collaboration, as documented by the Scripps Gerontology Center and the Aging and Disability Business Institute at the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging (n4a). Both financial risks and the “time it takes to establish a contract” were cited as barriers, and CBOs cited a need for more sophisticated data systems to contract with health care partners. The survey also found that CBOs seeking new business opportunities in the health care sector have often opted to join a “coordinated group of community-based organizations that pursues a regional or statewide contract with a health care entity” (Kunkel et al., 2017, and Kunkel et al., 2018). This shows a path forward to improve community infrastructure and financing opportunities for programs, attractive to both grantmakers and investors.

Building on new incentives and referral sources in the health care system, entrepreneurial community-anchored delivery systems can be flexibly designed to serve larger numbers of older and disabled adults – before the full impact of the age wave arrives. This could be done by encouraging partnerships among interested health care organizations, such as PACE and D-SNPs, to partner with CBOs in order to create linked networks that serve Medicare beneficiaries who need both health care and supportive services. Locally focused arrangements of this sort, which we refer to as Community-Based Health Organizations (CBHOs), could be developed and built out in grants for planning, piloting and dissemination.

Lawmakers Wrestle with Financing and Capacity Needs

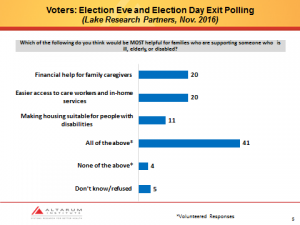

On Capitol Hill, policymakers are continuing to become more aware of the role of supportive services in eldercare. For example, in a November 2019 hearing before the U.S. House Ways & Means Committee, witnesses testified about improving nursing home and hospice quality, family caregiving, the growing number of older Americans with Alzheimer’s, and taking steps to build out long-term services and supports (LTSS). Altarum Senior Policy Analyst Joanne Lynn highlighted work conducted by UMass Boston and the Urban Institute that could undergird development of federal legislation that covers the “tail end” of long-term care risk using a social insurance model that could be financed by an additional 1 percentage-point increase in the Medicare payroll tax for workers older than 40. To cover “front end” risks, Dr. Lynn suggested testing a variety of options, including adding limited supportive services coverage to Medigap plans serving FFS beneficiaries, as is being considered in Minnesota.

Kickstarting New Collaboration

Over the next 10 years, Medicare service providers seem likely to move much further in the direction of integrating more services across settings and time, aligning with incentives provided by various contractual arrangements, bundles, and initiatives that pay health systems based on overall costs to Medicare. For community service organizations that serve the frail elderly population in traditional Medicare, new partnerships are now encouraged that can unlock new opportunities to expand service capacity and infrastructure. The question, for funders and entrepreneurs, is how to kickstart and optimize those collaborations among interested CBOs and health care organizations.

Varying configurations of CBOs and health care organizations are possible, allowing communities to design linkages for their needs. For example, some CBHOs might involve PACE programs, Medicare special needs plans (D-SNPs or C-SNPs), Medicare Advantage plans, larger health care systems, and Federally Qualified Health Centers and/or Rural Health Clinics. Fundamentally, such collaborations would have an anchor institution – one that has expertise in serving Medicare beneficiaries and a predictable source of revenue from CMS. The institution would collaborate with AAAs and CBOs to address the needs of high-risk Medicare and dually eligible beneficiaries who are identified as needing ongoing assistance and supportive services to remain at home (or other setting of choice). Contracts between an anchor organization and CBOs could be designed to both organize packages of services for older adults and to grow and gradually expand the number of older adults able to benefit from highly coordinated and comprehensive services. In addition to the satisfaction of improving care, organizations participating in a CBHO-type partnership might benefit financially through contractually apportioned shares of any savings realized.

For both health care organizations and CBOs, a new era is afoot. CBOs are poised to address health-related social needs for older adults with upstream interventions at much lower cost. This may spur health care innovators to see that investing (or reinvesting) in supportive services for aligned or enrolled Medicare beneficiaries makes good business sense, and where referrals to CBOs position medical practice to reap incentive payments, lower net business costs, and/or gain access to a share of savings. These insights, among others, are embedded in CMMI’s PCF and DC models, which are taking steps to encourage innovators to enter into formal relationships with CBOs. Similar relationships have already been fostered under private insurance plans and through Medicaid, but new flexibility in the approach to FFS Medicare beneficiaries with complex needs means that this important group of seniors is likely to be at the center of a new wave of contracting.

In the process, CBOs will need to make an accurate case for the value of their services; and, they will need to rapidly develop the capacity to both analyze and to share information with health care providers. Beyond that, they may find it in their interest to participate in organizational hub CBHO-type arrangements that handle financing, referrals, contracts and ongoing operational activities. From the beneficiary or client’s perspective, a CBHO could mean that services might be coordinated and delivered more reliably. CBHOs could also promote partnerships, not unlike ACOs, which act as hubs for various medical practices that are striving for improved coordination between settings and for greater efficiency.