by Adam Singer

Symptoms such as pain and confusion are very distressing for those nearing the end of life and their families. That’s why increasing attention to end-of-life care is spurring greater interest in alleviating such symptoms as a critical component of quality of life. Yet there is still a long way to go: a just-published in the Annals of Internal Medicine (https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M13-1609) finds there has been no improvement in the prevalence of common symptoms among end-of-life patients. In fact, many important symptoms — including pain and depression — have actually become more common.

In 1997, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a seminal report on the state of end-of-life care in the US that called for major changes in the organization and delivery of end-of-life care.[1] Many of the IOM’s indictments have ostensibly been addressed since that time through the expansion of palliative care and hospice, along with a greater focus on symptom management in both policy and practice. The Annals study was designed to ask whether end-of-life symptoms have become less prevalent from 1998 to 2010.

The study used data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative longitudinal survey of community-dwelling adults aged 51 or older (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/). Using an interview design, HRS collects information after each participant’s death from a proxy informant (usually a family member) about that individual’s end-of-life experience, including whether the person had any of the following eight symptoms for at least a month during the last year of life: pain, depression, periodic confusion, dyspnea, severe fatigue, incontinence, anorexia, and frequent vomiting. Using that information and the date of each participant’s death, the study analyzed the prevalence of each symptom over time for the population as a whole and also for subgroups that died suddenly or had cancer, congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic lung disease, or frailty.

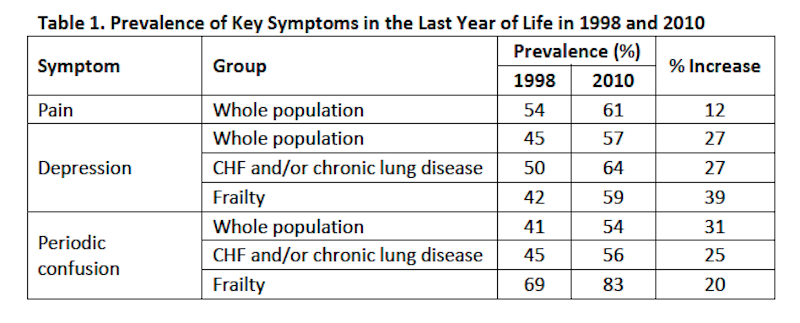

The study found that many alarming symptoms were common in the last year of life and affected more people from 1998 to 2010. For example, in the whole population, pain affected 54% in 1998 and 61% in 2010 (a 12% increase). Depression affected 45% in 1998 and 57% in 2010 (a 27% increase). Periodic confusion affected 41% in 1998 and 54% in 2010 (a 31% increase). Depression and periodic confusion also became more prevalent in subgroups with CHF and/or chronic lung disease and frailty. These results are summarized in Table 1 below.

In addition to the key results highlighted in Table 1, nearly all other symptoms in the whole population and in each of the subgroups trended toward increases in prevalence from 1998 to 2010, although most of these trends did not reach statistical significance. The one exception is that there were no significant changes in the subgroup with cancer.

High and worsening symptom prevalence near the end of life raises serious concerns about stubbornly ingrained shortcomings in end-of-life care despite the increasing national attention and resources being devoted to it. Indeed, recent studies of health care performance suggest that many providers continue to fall short in symptom management near the end of life.[2],[3],[4] The fact that pain remains common is particularly troubling, as this symptom is highly visible, well-studied, relatively reliably ameliorated, and has a large impact on health-related quality of life.[5] On the other hand, it is encouraging that trends in symptom prevalence in cancer may have stabilized.

While there have been many positive developments in end-of-life care since 1997, the Annals study shows that much more effort is needed to ensure that policy and organizational change translate to improvements in actual patient outcomes. Along these lines, there are many reasons why end-of-life symptom prevalence may not have improved since the IOM report:

- Intensity of treatment has been increasing near the end of life, and even though hospice use doubled from 2000 to 2009, the median stay is under three weeks.[6],[7] “Tacking on” hospice to otherwise intense late life care may leave patients suffering in the meantime and simply may not provide enough time for hospice to help alleviate symptoms.

- Palliative care services are more common in hospitals (where palliative care programs have tripled since 2000),[8] but most of the course of a terminal illness takes place outside of the hospital. Many patients may not have consistent access to palliative services known to be effective in promoting symptomatic relief.

- Effective treatments exist for many end-of-life symptoms, but there are significant gaps in their delivery.[9],[10] Interventions may not be reaching the right patients in the right ways.

In summary, the prevalence of many end-of-life symptoms remains unacceptably and disappointingly high in light of active efforts to improve end-of-life care. Some best practices simply are not being followed. Some choices are not being adequately explained and offered to patients and the family caregivers supporting them. Aligning current care with best practices represents a promising way to harvest low-hanging fruit in order to reverse these negative trends and reduce end-of-life symptom burden for millions of Americans. But beyond that, the trends characterized in the Annals study must be parsed further in order to identify better and more coordinated ways to organize and deliver high-quality end-of-life symptom management.

Footnotes:

References

[1] Approaching death: Improving care at the end of life. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine; 1997.

[2] Walling, A.M., Asch, S.M., Lorenz, K.A., et al. The quality of care provided to hospitalized patients at the end of life. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1057-1063.

[3] Dy, S.M., Asch, S.M., Lorenz, K.A., et al. Quality of end-of-life care for patients with advanced cancer in an academic medical center. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):451-457.

[4] Malin, J.L., O’Neill, S.M., Asch, S.M., et al. Quality of supportive care for patients with advanced cancer in a VA medical center. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(5):573-577.

[5] Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine;2011.

[6] Teno, J.M., Gozalo, P.L., Bynum, J.P., et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009.JAMA. 2013;309(5):470-477.

[7] NHPCO facts and figures: Hospice care in America. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization;2014.

[8] Growth of palliative care in U.S. hospitals: 2014 snapshot. New York, NY: Center to Advance Palliative Care;2014.

[9] Walling, A.M., Asch, S.M., Lorenz, K.A., et al. The quality of supportive care among inpatients dying with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(9):2189-2194.

[10] Walling, A.M., Tisnado, D., Asch, S.M., et al. The quality of supportive cancer care in the veterans affairs health system and targets for improvement. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2071-2079.