By Anne Montgomery

Time is growing short to make big changes to basic processes for service delivery to elders, who will soon constitute one-fifth of the U.S. population. Basically, we have a mismatch between the health care delivery system and what many older adults actually need.

Typically, older adults typically see multiple clinicians working in many settings – e.g., primary and specialty care, hospital care and home care — and communication between these providers tends to be inadequate. This in turn contributes to fragmented care that can be frustrating and costly. Medical services are often disconnected from the life goals and treatment preferences of a given individual, and his or her need for various supportive services are often not documented. Finally, although numerous smaller-scale initiatives have shown that much of the disability and frailty associated with aging can be effectively managed (and sometimes delayed or prevented), innovative models that prioritize these goals have not yet been widely implemented.

This suggests it’s a good moment for policymakers to consider piloting designated entities, perhaps called community-based health organizations (CBHOs), in order to organize provision of cost-effective supports across a population of high-risk, high-cost elders living in a given area or region. Broadly similar to a model developed by Joanne Lynn, MediCaring Communities, [https://medicaring.org/book-online/] CBHOs, operating as an interconnecting network, could be chartered to prevent and delay more costly inpatient and institutional care, working in partnership with local medical care providers. They would likely begin at a modest scale, forming networks in order to further develop business acumen, acquire information technology that is essential for interoperability, and develop collaborative relationships and contractual arrangements that over time can transition into more formal integrated care systems. As a distinguishing characteristic, CBHOs could measure and reinvest savings in improving community care systems.

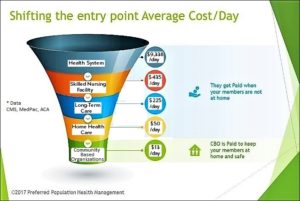

One intriguing graphic, created by Preferred Population Health Management and reprinted here with permission, provides an illustration in one community of how delivery system entry points and costs might be re-thought. For vulnerable populations, which includes many older adults, it may make sense to consider looking at community-based organizations (CBOs) or Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs), as another entry point to a more tightly coordinated care system that prioritizes cost-effective services that reduce the risk of needing higher-cost interventions.

Using grant funding, CBHOs could be charged with standing up coordinated, synergistic delivery systems for older adults and individuals with disabilities across a service area. Collaborations could take various forms: partnerships between AAAs/CBOs and PACE organizations; with Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs); with Rural Health Clinics (RHCs), and other possible combinations. CBHOs would be tasked with analyzing available data on the needs of all older adults and individuals with disabilities who live in the area, filling in with more complete data over time. They would then create a five-year plan for serving older adults in the area, with approval requiring consultation and sign-off by a local coalition representing providers, advocates, and individuals currently needing (and/or anticipating needing) services. Approved grant funding would flow to CBHOs, and states would be asked to assist in tracking CBHOs and their performance vis-à-vis standardized metrics, costs, and outcomes for individuals. At the expiration of the grant period, the federal government, in consultation with states and community stakeholders, would determine which CBHOs could become permanent.

There are several indications that policymakers are starting to consider such approaches. For example, a Senate draft of the Older Americans Act reauthorization, which is now circulating for comment, includes language stipulating that future OAA demonstration projects must address determinants of health; reduce health care expenditures, “preserve or enhance” quality of care to individuals, and prioritize initiatives that focus on caregiver support, multigenerational engagement and community-based partnerships.

There are other hopeful signs in work that is being led by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), which is teeing up a range of possible alternative payment models, and adaptations of existing programs to recognize and address social determinants of health in vulnerable populations. For example, as noted in our blog last month, [https://medicaring.org/2019/05/08/2019-cmmi-proposals/] CMMI has announced two groups of models, called Primary Care First and Direct Contracting. As part of the Direct Contracting Model track, CMMI published a Request for Information on how geographic contracting could work. Because they are typically limited to services that are available locally, older adults living with serious chronic illnesses and functional limitations and younger people with disabilities are populations that would be well-suited for a geographically-organized care model.

If local governments were allowed to be contractors, this could open up new opportunities for the Aging Network. To date, nearly all major federal innovation efforts have been geared toward large organizations working within the medical care system, but this could change. About half of AAAs are embedded in local governments, and AAAs and CBOs already understand how supportive services for older adults and other vulnerable populations can be efficiently delivered in very different types of communities. Moreover, as the nation’s primary publicly-funded network of community-based supportive services providers, staff are trained to organize and provide services in the home, and are therefore attuned to the life circumstances of individual elders.

In another encouraging development, CMS published an updated Scope of Work (SOW) in March for organizations applying to be Quality Improvement Organizations/Quality Innovation Networks (QIOs/QINs). Notably, this SOW instructs applicants to “coordinate with existing community-based efforts and reach community stakeholders to form community coalitions…[that] include the recruitment and engagement of providers across all care settings” — including those delivering community-based supportive services. QIN-QIOs will be required to use “a population based measurement strategy to show targeted improvement of beneficiaries that reside within specified ZIP codes” and to reach at least 414 community coalitions across the country. This means that QINs/QIOs will be actively supporting organizing of community stakeholders (providers, beneficiaries, caregivers and their families, emergency responders and more) in order to gather data that aims to improve care transitions and achieve specific reduction targets in high-cost inpatient hospital utilization.

By 2035, there will be 80 million older adults 65+ in the U.S., and the population age 85 and older will reach 12 million. And since many older adults have complex social needs and about one-third are living with a disability, this is an important time to try to shift the pattern of services further toward provision of home-based medical care and a more organized system of supportive, flexible, community-anchored services.

If we do too little now to deliberately boost the ability of the supportive services sector to innovate, it seems likely that unmet need for basic supports among many community-dwelling elders in the large boomer cohort will skyrocket. If this happens, health care costs will likely balloon. To help forward-thinking pioneers in this sector move forward faster, let’s hope that policymakers will give a green light to spurring development of collaborative, population-based care systems that are mission-driven to keep older adults at home and out of medical crisis for as long as possible. It’s a doable challenge, and the potential societal return on investment is large.