Another in our series to build the MediCaring book. Judith R. Peres contributed significantly to this post. Please feel free to comment, expand, tell us what we’ve got right, and what we have missed.

For decades, older adults have relied on the medical system to cure or treat what ails them; but those aging into advanced age will soon discover that what they most need—and most cannot afford or find—are social services that deliver essentials, such as food, safe housing, and reliable transportation, as well as hands-on, personal care for activities of daily living.

Our healthcare system has long delivered—and paid for–the most advanced, most expensive medical tests and treatments, with little regard to their cost. Consider, for instance, our willingness to pay for the very latest cancer drug for very old people, even when it costs $100,000 per treatment, and even when it yields little improvement to quality of life or length of life.

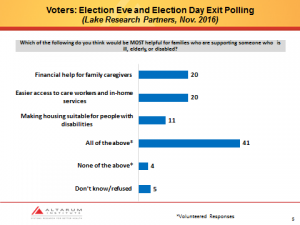

And while we are keen to prop people up with medical treatments, we balk at paying for what very old people need most: housing, food, transportation, and personal care. Only when an individual has virtually no assets left does Medicaid’s safety net kick in and help out. And even then, that help may be insufficient, particularly for services delivered in the home. Recent economic and political challenges have threatened the very fiber of that safety net, and millions of older Americans have found themselves wait-listed for food. Estimating the suffering and financial costs of these arrangements, as compared with a more optimal set of services, is difficult; but, by any metric, the magnitude of waste and unnecessary suffering is enormous.

Medicalization of Care: Leaving Frail Elders Behind

Traditionally, our social arrangements have separated medical services from social services, or long-term care (LTC). And neither of these has really been linked to services that guarantee adequate and safe housing environments. But for frail elders to thrive, these circles of care must become concentric and collaborative.

Imagine, for instance, what happens to a still-not-back-to-functioning frail elder who is discharged from the hospital. She gets home to a house that still includes stairs at the front door, or bathroom doors too narrow for her wheelchair or walker. Or consider the heart failure patient discharged from the emergency department, who is waitlisted for Meals on Wheels and, in the meantime, can only afford canned vegetables or soups laden with sodium. These all-too-common situations reflect failures of coordination that eventually cause healthcare setbacks, trigger re-hospitalizations, increase suffering, and lead to very high costs. With coherent care planning among spheres of care and influence, all of this could have been avoided—and better outcomes attained.

Rather than focusing only our open-ended payments for medical treatment, we should consider investing more in housing, nutrition, livable communities, caregiver support, and other services for frail elders. While most developed countries spend about 1.7 times as much on social services as on medical care, the U.S. spends only about 70% as much on social services as on medical care. (Bradley and Taylor, 2013) This medicalization of care affects frail elders particularly hard, since they need help that goes beyond medication, and includes help with the ordinary tasks of daily life, such as eating, bathing and moving around. Who could deny that accomplishing these are, in fact, essential elements for a decent, dignified old age?

Aging in Place Will Require Doctor Housecalls—But So Much More

Aging Boomers, all 80 million of them, imagine and hope that they will be able to age in place, remain in their own homes and neighborhoods rather than moving to a nursing home. To achieve this, they will need a score of services that span medical and social supports, from needed include care coordination, medication management, home health and hospice, durable medical equipment, and telemonitoring and management, to personal care assistant service, such as those offered by homemaker and personal care agency services; home-delivered meals; home reconfiguration or renovation; transportation and more. Social services must also help their family caregivers, providing them training, respite, and support.

In the same way that pediatrics and obstetrics recognize that certain services are required to meet the unique needs of these phases of life, serving frail elders well entails an approach that proposes to make certain common sense modifications to the way services are delivered. This includes services that are paid for privately, publicly financed services provided by Medicare and Medicaid, those financed by the Older Americans Act and related state and community programs, and housing initiatives.

We term this approach MediCaring, which uses geriatric principles and palliative care standards and approaches – but expands to include a real focus on moving resources to cover essential social services. Imagine the elders described above. The first would have been referred to services to help pay for and modify the home to make it safe and accessible. The second would have had immediate access to nutritious, home-delivered meals.

At the same time, frail elders are likely to need help with medication management, and support for taking medications whenever a capable caregiver is not present, for instance, or a diet adjusted to fit whatever his or her personal care assistant can cook. Elders and their families will surely need to consider how to handle the finances of long-term survival with worsening dependency, and how to deal with the next exacerbation of a chronic condition that could justify hospital care but might be better treated at home.

Some health information exchanges are beginning to include social services information –a major step forward. All Area Agencies on Aging and Aging and Disability Resource Centers maintain a catalog of services in their community, though medical providers often do not realize just how valuable these services are. As they are being developed today, community-based teams that are working to implement variations of the MediCaring model are also closely engaged in shaping the availability and quality of both health and social services – both to arrange services for frail elders who need them, and to help set priorities for the most appropriate and cost-effective interventions available in their communities. It is a step forward—but we also need a leap.

Bradely, EH, and Taylor, LA. The American Healthcare Paradox: How Spending More is Getting Us Less. Academy Health Presentation, 2013. Accessed online at https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/american-health-care-paradox-why-spending-more-getting-us-less on April 24, 2014.

keywords: MediCaring book, Judy Peres, Judith Peres, Joanne Lynn, Janice Lynch Schuster