By CECAI and Caring Across Generations Staff

Caring for others has become the defining issue of our time, and grows increasingly salient in political campaigns with each passing day. This emerged as the defining theme of a November 14th forum, “America CARES,” which was headlined by Altarum Institute’s Center for Elder Care and Advanced Illness and Caring Across Generations.

Coming less than one week after the national election, more than 200 caregivers, researchers, analysts, and advocates gathered online and in person in Washington, D.C., to discuss voter preferences, share information about what stakeholders and advocates are prioritizing, and focus on what can be moved forward through deliberate collaborative work.

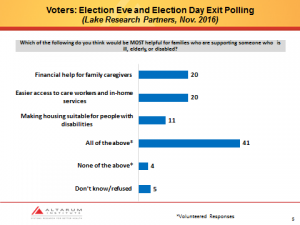

Much attention was paid to what voters think, as measured in bipartisan national polling conducted on election eve and election day by Lake Research Partners (LRP):

As both LRP principal Celinda Lake, a Democratic pollster, and Brian Nienaber of The Tarrance Group, a GOP pollster emphasized, the most striking finding is that both Trump and Clinton voters overwhelmingly chose “all of the above.”

“When you look across these demographics, this [caregiving] issue is of major salience to groups in both coalitions,” Lake said. Women care particularly intensely about this issue, [and] so do seniors.” She continued: “This issue needs to be embedded in a broader economic frame. We are talking about it in too minor a way.” Nienaber added: “When you get people volunteering ‘all of the above’ that is huge…[It] is one indicator that [voters] grasp the depth of the problem, and I think too an indicator that they are just not sort of fully versed in what the most appropriate or easiest bite-sized solution is.”

For this reason, Lake suggested that messaging on this issue should always be “1/3 problem, 2/3 solution.” As Josie Kalipeni of Caring Across put it, “[It] creates an umbrella to say that we need a system that works for all…and to have a unified message while bringing expertise of what [each organization] is advocating for to the table.” Moreover, a third of respondents favored all three options presented for expanding the number of direct care workers: increasing wages to $15 per hour, benefits including paid time off and retirement savings, and opportunities for skills training and career advancement.

What voters say they want are the things we don’t have in place in our health care system today—except for in-home services—and these are not reliably available or affordable for many people. The system that we have in place today, in other words, is effectively not the one we need in a rapidly aging society.

But there is also good news: Kevin Simowitz of Caring Across Generations pointed out, “caregiving entered the presidential campaigns this year in a way we haven’t seen it enter before,” with care appearing on both the Republican and Democratic national party platforms (for more on how this happened, see the Family Caregiver Platform Project). Multiple speakers reiterated the need to make an economic case for care policy in combination with stories about the people impacted. As Ben Chin of the Maine People’s Alliance pointed out, “the public is with us on tax fairness right now. “Maine People’s Alliance managed to get a measure on the ballot in 2016 that provided 3% surcharge on income over $200,000 to fund education. “In districts where many voted for a right wing populist, they did vote for this,” he said. This dynamic can be used again, he argued, noting that polling from Caring Across Generations has found broad bipartisan support for universal family care funded by tax increases on those making more than $100,000.

In a new long-term care white paper, Caring Across Generations recommends the creation of a state level public long-term services and supports benefit that is accessible to all who need it regardless of income. “We continue to see tremendous opportunities in the states, and we believe that states can and must take intermediate steps to expand access to affordable and accessible long-term care until federal improvements are made,” said Sarita Gupta, co-director of Caring Across Generations. “State-based programs can address the unique care problems faced within each individual state, yield invaluable insights into what works and what does not, and build momentum for an eventual federal solution.”

The fact that people want much more integrated and well-coordinated care was also clearly reflected in responses to an online survey of registered participants fielded by Altarum. Participants were asked to rate their support for a number of policies. Of the 5 most that were most strongly supported, 4 out of 5 related to coordination of support: 1) ensuring availability of adapted housing; 2) development of a comprehensive repository of social resources and the community level; 3) caregiver assessment in Medicaid, Medicare, and the VA; 4) flexible workplace policies; and 5) expansion of integrated, community-based programs such as the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE).

To establish a system that is effective, we need to adapt, re-engineer and redesign to include health-related social services and supports in the array of services that are available on a reliable basis. Roughly 70% of us will spend several years—and for some it will be many years—living with both multiple chronic conditions and functional limitations.

We know that 34 million family caregivers and 2.2 million care workers provide care to older adults and people with disabilities in the community. Both groups struggle to maintain financial stability, to coordinate care, to maintain physical and mental well-being, and to balance their work and family responsibilities,

The most prominent theme of the forum was that care is a unifying issue that provides a blueprint for tailoring positive advocacy in a more populist era. Again and again, speakers emphasized the universality of the need for care. Noting that there will be 47 mayoral elections and 36 gubernatorial elections in 2018, Lake suggested that advocates, analysts, stakeholders and their allies have a solid opportunity to make caregiving actionable at the ballot box. Participants also highlighted the Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act as evidence of what can be accomplished at the state level, in addition to the ways in which care transcends partisan politics. This bill would require that hospitals record the name of the caregiver in the medical record, inform them if the loved one is transferred, and provide instructions and training on tasks that the caregiver will be expected to perform at home. The traditionally red state of Oklahoma, John Schall of Caregiver Action Network noted, was the first state to pass the CARE Act.

Voters have provided a green light to move forward—at the national level, the state level, and the local level. And we look forward to working with all of you to do that. Together we have a clear opportunity to shape policy and to ensure that those who care, whether as unpaid family members or as workers, live in dignity and have the tools they need to support those for whom they care.