4.1 What are long-term services and supports (LTSS)?

Despite surveys that indicate our overwhelming preference to grow old, live independently, and die in our own homes,[115] we will mostly face old age encumbered by multiple complex health conditions; and we will, at one time or another, need some long-term services and supports. If we hope to stay at home—or, at least, to stay in the community and not in an institution—we will need services that support independence, including home-delivered food, adapted transportation, disability-appropriate and affordable housing, personal care assistance, help to manage finances, and support for voluntary caregivers. We will need health care, to be sure, but we will also need help in order to accomplish everyday activities that we have been used to doing for ourselves when we were simply ordinary independent adults. Some of us will, eventually, need more comprehensive support than can reasonably be provided at home and will need to move into a facility that can provide long-term care services, which might be housing with services on-site, an assisted living facility, or a nursing home.

Consider, for instance, a still-recovering frail elder upon discharge from the hospital. She gets home to a house that has stairs at the front door that she cannot climb (in or out), or bathroom doors too narrow for her wheelchair or walker, and her kitchen stinks from the food left in disarray when the ambulance crew transported her out. Or consider the heart failure patient discharged from the emergency department who must wait 6 months for Meals on Wheels and, in the meantime, can only obtain canned meat and vegetables or fast food laden with salt. Both of these patients need an attentive friend or family member who will help out, but they have no one. These all-too-common situations eventually cause healthcare setbacks, trigger re-hospitalizations, increase suffering, and lead to very high costs.[116] With coherent planning across spheres of care and influence, and buttressing of LTSS availability, these errors could have been avoided—and elderly people could live better at lower cost.

The services often included as part of LTSS are as follows:

- Care coordination/case management/navigation

- Personal care (baths, toenail cutting, hairdressing, bed changing)

- Homemaker services (cleaning, cooking)

- Home hospice

- Adult day care and day hospital services

- Home-delivered meals or food

- Meals at congregate sites

- Home reconfiguration or renovation (ramps, lighting, grab bars, toilets)

- Caregiver skills education, group support, respite

- Medication management (loading pill dispensers, ensuring access to medications)

- Skilled nursing (wound care, handling special medications or devices)

- Telephone reassurance and monitoring services

- Technologies that promote connectivity

- Emergency and urgent advice and help for non-medical issues

- Equipment rental and exchange

- Adapted transportation, door-to-door

- Help with legal and financial issues

- Investigating potential abuse, fraud, or neglect

- Counseling to improve family dynamics

- Friendly visitors and telephone networks for socialization

- Socialization (calling networks, neighborly check-ins, group activities)

If a person has the good fortune to live in a community that has insisted on ensuring nutrition for all or has been pursuing universal design in all new and remodeled housing, frail elders in that community will have many more options and much more confidence, compared with elderly persons living in a community that has not acted to address these issues.[117] So much of what happens for supporting frail elderly people depends upon community action. No one person can make the food delivery wait list disappear, or train a cadre of aides with skills to deal with dementia, or have a responsive agency to investigate and alleviate neglect or abuse. Indeed, no one nursing home resident or family member can substantially improve the quality of care in a nursing home. These things have to be done for the affected population of frail elders, usually defined by where they live.

When Medicare and Medicaid passed in 1965, the vision of a safe and supported old age required a third component, the Older Americans Act (OAA) , which was to provide an array of services to support elderly people at home. The OAA was not means-tested. It meant to provide federal support to local initiatives that would provide supportive services. OAA funding has generated the national network of Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) , which must provide referrals to services in their areas and may directly provide services as well.[118] The Administration on Aging (AoA) works in partnership with State and Area Agencies on Aging to provide the Eldercare Locator database, a public database of potentially available services which is available at eldercare.gov.

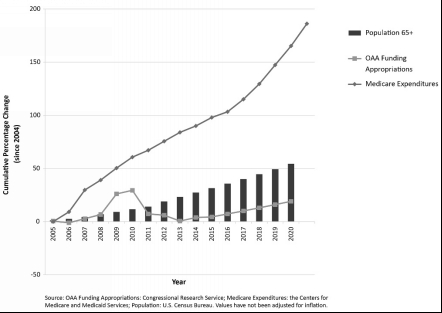

OAA funding, along with supervision by the federal ACL and coordination by the AAA local entities, and supplemented by state and local initiatives and philanthropic contributions, has generated the “aging services network,” a fragile and unofficial patchwork of mostly non-profit charities and businesses providing services in communities nationwide. These agencies take on all sorts of supportive endeavors, from helping elders to file their taxes to finding volunteers to build a wheelchair ramp, and from assessing the home environment for safety to providing respite for exhausted caregivers. Obviously, such a panoply of thinly funded and uncoordinated endeavors can leave some needs unaddressed and others met with inadequate reliability and skill. The OAA funding levels have increased far less than inflation alone and dramatically less than the population growth. Therefore, waiting lists have arisen for most services, and some, like respite for caregivers, only exist in very limited special programs.

The following graph illustrates the growth of the aging population in relation to changes in OAA funding and total Medicare expenditures.

Figure 4.3: Growth of the Aging Population Compared with Changes in OAA Funding and Medicare Spending[119]

LTSS discussions usually focus on what are called “concrete services,” those that yield specific, observable actions or products. However, elderly people often have a high priority for socialization itself: having someone to listen when a person needs to talk, sharing worries and fears as well as fun, and providing love and affection.[120] Often frail elders find their lives increasingly isolated as spouses and friends become ill and die, driving becomes restricted, and physical limitations make it harder to socialize. The sense of belonging as well as the warmth, nurturing and assistance with information and problem-solving that come with human interaction are all components that contribute to a frail elder’s well-being and often are no longer available without some organized community-based supportive services.

[115] (Harrell, et al. 2014)

[116] (Seligman, et al. 2014)

[117] (Oosting 2014)

[118] (Administration on Aging, Administration for Community Living, Eldercare Locator n.d.)

[119] Figure 4.3 is based on data presented in N Engl J Med 373;5 (nejm.org), Ravi B. Parikh, M.D., M.P.P., Anne Montgomery, M.S., and Joanne Lynn, M.D., The Older Americans Act at 50—Community-Based Care in a Value-Driven Era, July 30, 2015, pp. 399-401. Copyright © 2015 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission. Data source for OAA Funding Appropriations is from: Congressional Research Service; Medicare Expenditures: the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Population: U.S. Census Bureau. Values have not been adjusted for inflation. Projection for OAA appropriations assumes linear growth at the same rate of FY2015 to FY2016, based on the President’s budget.

[120] (Hogan, Linden and Najarian 2002)