2.1 What processes are essential in generating good care plans?

Developing a good care plan, and doing it efficiently and effectively for a great many complicated situations, is difficult. Perhaps that is why we have no examples of good care planning processes brought to scale for a sizable population of frail elders. Of course, barriers also arise from having no reimbursement tied to comprehensive care planning and having most of the key members of the care team dispersed geographically with no personal relationship with one another. These conditions are exactly what need to change. Without a good care plan being created and implemented, the elderly person is constantly caught in a reactive mode of responses to whatever calamities arise and constant anxiety. In contrast, a good care plan ensures thoughtful preparation to support the person through likely situations. Having many people with good care plans in a community will ensure that services come to be organized to deliver on whatever is most important to frail elderly persons and their families. The consequences of the gaps between current dysfunctions and good care practices are often starkly clear. For example:

- A frail elder with a good care plan will have a back-up plan in case a family caregiver becomes ill; a frail elder in the usual care system will be transported to the emergency room when the caregiver is suddenly unavailable.

- A frail elder with a good care plan peaceably dies at home and loved ones are present or notified; a frail elder in the usual care gets a painful and expensive assault by well-meaning emergency responders who have no choice but to try resuscitation and rescue.

A good care plan must address expected situations requiring rapid decision making, such as appropriate response to cardiac arrest and death, and must deal with recurrent problematic treatment issues, such as hospitalization or artificial nutrition. But care plans are not just for medical treatments. They also honor personally meaningful relationships and activities, document trade-offs between medical treatment and life enjoyment, and build on the availability and skills of family and other caregivers. The care plan must move with the patient across settings and time, be revised as situations change and at planned intervals, and be evaluated for achievement of goals. Evaluations of the care planning process and the care plans should be reported to service providers involved in the planning, so their work can improve.

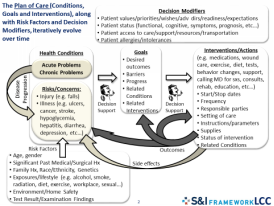

A set of voluntary committees sponsored by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology recently has been working to build care plans into health records. Figure 2.1, their summary graphic concerning care plans, helps to anchor the MediCaring approach to care plans.[33]

Medicare proposed a reasonable suggested list of care plan elements in their regulation establishing the CCM payment code.[34] This includes:

- A problem list,

- Expected outcome and prognosis,

- Measurable treatment goals,

- Symptom management and planned interventions,

- Medication management,

- Community/social services to be accessed,

- Plan for care coordination with other providers,

- Responsible individual for each intervention, and

- Requirements for periodic review/revision.

A list like this probably seems so obvious that the usual patient assumes that it is in effect, and the complexities in the graphic might make the exercise appear daunting. However, complicated situations require solutions that do not oversimplify. Frail elders and their families deserve to expect that their care team functions as a team, thinks clearly about the future, makes useful recommendations, and respects the elderly person’s priorities. The challenge is to build a delivery system that can regularly, efficiently, and competently deliver on that vision.

Figure 2.1: Care Plan Diagram

[Graphic provided by S&I Framework LCC]

Read more about:

2.1.1 Understanding the frail elder’s situation

2.1.2 Coming to accord on goals and services

2.1.3 Setting parameters for re-evaluation

2.1.4 Assuring availability of the care plan across settings, providers, and time

2.1.5 Dealing with difficulties in care planning

[33] (Garber, L and the S & I Framework 2014)

[34] (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Chronic Care Management Regulation, 79 FR 67715 2014)